New research from Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) has shown that gut and bloodstream infections are caused by the same bacteria, offering hope of better prevention and diagnosis of deadly neonatal sepsis.

Bloodstream infections are a leading cause of hospitalisation and death in children under five, with the highest burden in sub-Saharan Africa. In newborns, the risk is even greater because their immature immune systems can allow typically harmless gut bacteria to invade the blood and cause severe sepsis. Despite the scale of the problem, identifying the source of these infections has been difficult.

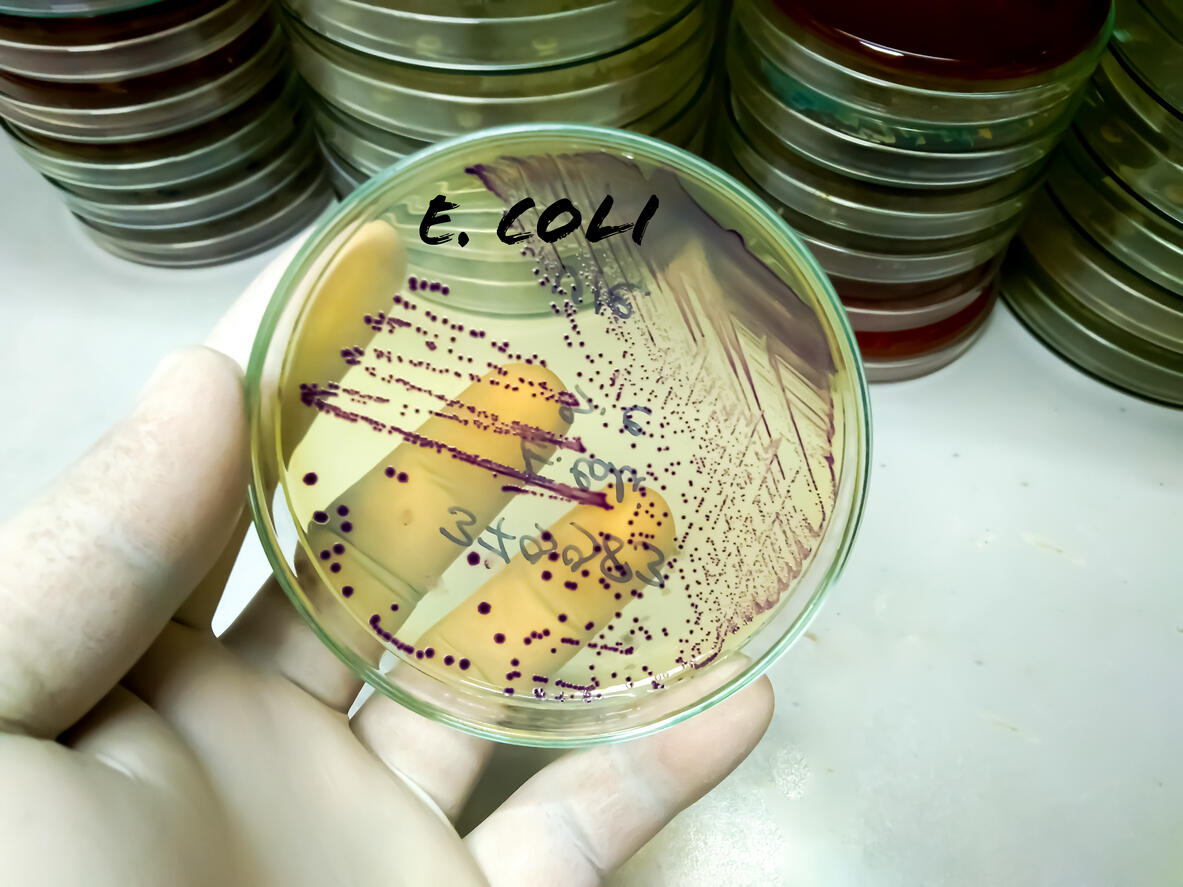

In this study, published in Communications Biology, researchers from LSTM, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Tanzania, and the University of Bergen, Norway, compared the genomes of two dangerous bacteria, Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Klebsiella pneumoniae, isolated from blood and faecal samples from Tanzanian newborns admitted with fever.

The team DNA sequenced the samples, and in the majority of cases, the bacteria were almost genetically identical, suggesting that the same strain had moved from the gastrointestinal tract into the blood. There was also a bacterial strain that acquired an antimicrobial resistance (AMR) gene between the gut and the blood, a concerning development which limits treatment options.

These findings will support future diagnostic strategies, as stool samples are far easier to collect from newborns than blood samples, allowing clinicians to identify infants at risk of sepsis. This development would be vital for very low birthweight babies or those in neonatal units where sepsis and AMR outbreaks can be deadly.

Dr Richard Goodman, the paper's lead author and a Post-Doctoral Research Associate at LSTM, said: "Our findings confirm that the bacteria causing bloodstream infections are often genetically identical to those found in the patient's gut. This supports the idea that the gut acts as a reservoir for these infections. Understanding the genetic markers associated with this transition is essential for designing interventions that protect the most vulnerable children."

The study revealed that many of the genes required for survival in the bloodstream were already present in the gut strains, including key iron-uptake systems that enable bacteria to thrive in blood. Researchers also showed that stress from moving between environments may trigger shifts in bacterial genomes, including the development ofAMR.

Dr Sabrina Moyo: "Improving early detection of high-risk bacteria could help clinicians act sooner and potentially prevent life-threatening infections. This is especially important in hospitals where diagnostic resources are limited, and sepsis can progress rapidly."

The study highlights the need for further research to determine why bacteria move. It underscores the need for improved surveillance, targeted antibiotic strategies and interventions that prevent infections before they begin, essential steps for reducing newborn deaths and slowing the spread of AMR.