Priya Garg,

DTMH 2015

‘If the plague spread– it could be a modern rewrite of our history books’

One of the most devastating pandemics of mankind, the zoonotic safety-pin shaped bacterium Yersinia pestis, swept across Europe in the Middle Ages, carried on the back of the innocuous, silky black rat via the Oriental rat flea Xenopsylla cheopis, or coughed out in aerosolised droplets from the lungs in pneumonic form, causing tens of millions of deaths from the plague and leaving countries reeling socially and economically, from its startling impact.

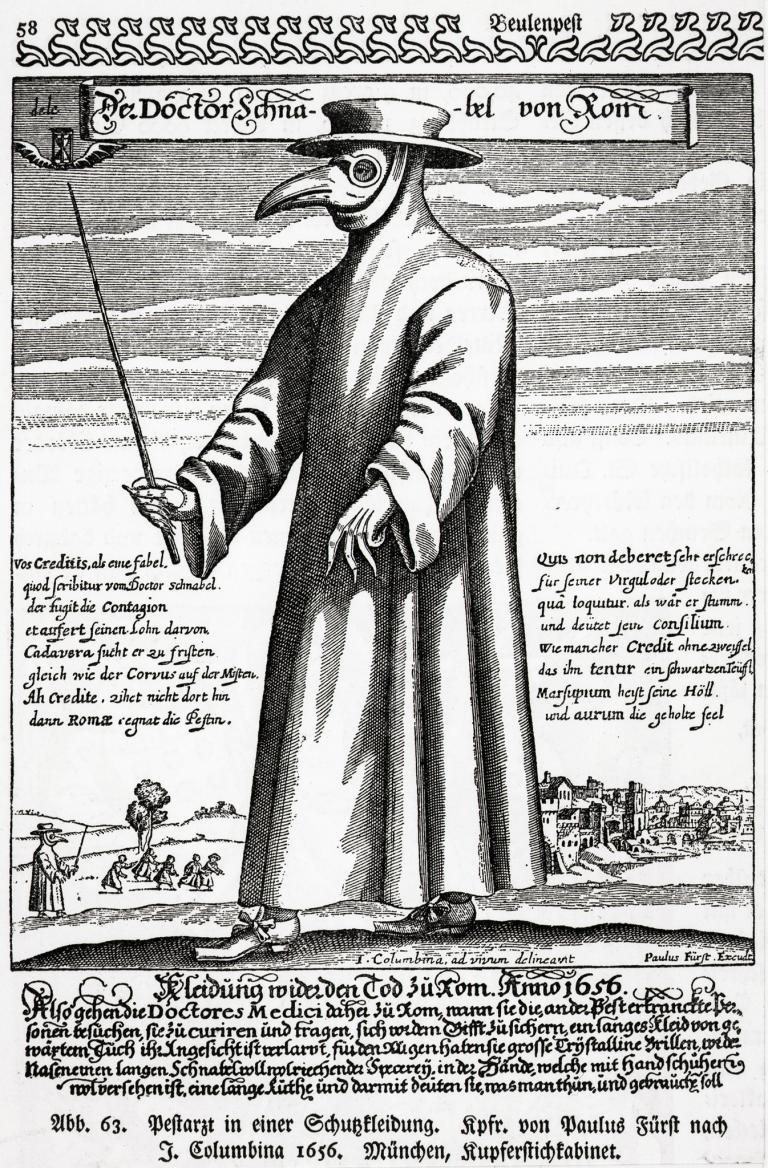

Thought to be carried across the old trading routes, it stowed away in compartments of merchant ships, lurking amongst the cabins and berths. Imprinted in its wake was a terrifying legacy of large red crosses painted across the wooden doors of London Elizabethan housing quarantining the infected, physicians with waxed fabric overcoats and beaked costumes steeped in posies of scented materials to ‘ward off’ supposed evil spirits, swollen, painful buboes and gruesome nocturnal death carts carrying the piled bodies of the dead.

Yersinia’s discovery in decaying Bronze Age skeletons suggests it is over thousands of years old, yet as recently as September 2015, it was tucked into the highlands of Madagascar, amongst cobbled streets and coloured plastered buildings in the rural township of the Moramanga district, where the Ministry of Health notified the WHO of an outbreak. A disease confined supposedly to the yellowing pages of our history books.

In fact, since the early 1990s the incidence of the human plague globally has been on the rise. From 2000, plague outbreaks have been reported in Zambia, India, Algeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, China, Peru and Madagascar, and subsequently, it has been officially recognised as a re-emerging disease.

In some of our final clinical seminars before the looming DTM&H exams, we looked at a relief map of Madagascar, analysing how we as practitioners, might help deal with an outbreak of the potentially lethal plague, noticing the proximity of the confirmed cases to the over-spilling urban slums, the vulnerable prisons coping with large numbers of rats within their confines and swathes of high population densities with poor hygiene and sanitation. Additionally, we heard about growing worries of the plague travelling again to Madagascar’s capital, Antananarivo, where people live in their hundreds of thousands, and amassing fears of what it may spark if it did indeed establish a foothold in the city.

Although antibiotic treatment exists and is effective, there are also increasing signs of burgeoning antimicrobial resistance due to plasmid transfer and a worrying possibility that Deltamethrin insecticide resistant flea numbers may be spreading. Initially causing flu-like symptoms, incredibly infectious, untreated, the plague is rapidly fatal, and can lead to a significant gangrenous septicaemia.

As of the 30th August there were 14 cases of the plague notified in Madagascar and 10 deaths, all in the pneumonic form, where mortality can occur within 24 hours. Interestingly, there have also been 11 cases of human plague reported in the USA since April.

The August Madagascar outbreak follows a previous bout of the plague between 2014-15 with over 335 cases and 79 deaths. This lead to a grant in February 2015 of 1 million US dollars from the African Development Bank to support the containment of the plague and strengthen the response capacity in Madagascar, using methods of surveillance, vector control, prophylactic management of contacts & isolation, which remain our main tools against it.

Yet, if public health measures prove ineffective and the plague casts its shadow, could this supposedly ancient disease continue to resurface as a significant impending threat of the 21st century?

Good luck with exams DTM&H.