World Malaria Day 2023

“Time to deliver zero malaria: invest, innovate, implement”

Overview: 2023 - fight against malaria across Africa

Professor Sarah Staedke

In September 2022, I joined LSTM as a Professor of Malaria and Global Health based in Kisumu, Kenya with the KEMRI (Kenya Medical Research Institute)-CDC (US Centers for Disease Control)-LSTM collaboration. My research explores new ways to control malaria in Kenya and Uganda.

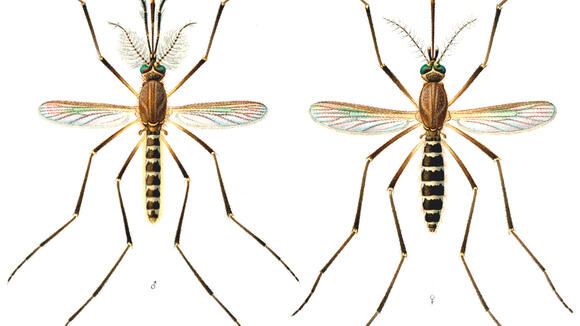

In the areas where we work, malaria is a major health problem. Malaria is transmitted year-round, and the mosquitoes that transmit malaria are very efficient (and clever). People can be infected with malaria repeatedly, especially young children, and are at constant risk of illness, severe disease, and death due to malaria.

To control malaria, we can try to reduce exposure to infected mosquitoes, treat people with malaria medicines to prevent or clear parasites, and use vaccines to strengthen children’s immunity against malaria. My research is focused on new approaches to control mosquito vectors and reduce transmission.

In western Kenya, we are conducting a large trial of ‘attractive targeted sugar bait’ (ATSB) stations in 70 clusters of villages near Lake Victoria. ATSBs are A4-sized panels containing thickened fruit syrup laced with an insecticide, which are hung on the outside of households. ATSBs are designed to attract and kill mosquitoes, and could be used alongside other methods to prevent malaria, like bednets.

To determine if the ATSBs are effective, we are following children aged 1-15 years to compare the number of malaria episodes that occur in children from the villages where ATSBs are hung, to those from villages without ATSBs. The study started in March 2022 and will continue until March 2024.

Over the past year, we have distributed over 200,000 ATSB stations, and followed 1,969 children in our cohort studies who completed 14,765 clinic visits. At enrollment 47% of cohort children tested positive for malaria parasites and 928 episodes of malaria have been diagnosed during follow-up, indicating the high burden of malaria in this area and need to intensify control. Over the next year, we will continue to monitor the ATSB stations, follow-up children in our cohort study, survey the communities in the study area, study mosquitoes, and talk to community members to better understand their perceptions of ATSBs.

In Uganda, we are conducting a trial of bednets distributed by the Ugandan Ministry of Health in 64 communities across 32 districts. Traditionally, bednets have been treated only with pyrethoids, but mosquitoes have become resistant to this commonly used insecticide. We are comparing new types of nets that incorporate pyrethroid insecticides plus additional chemicals, including the synergist piperonyl butoxide (PBO LLINs) and pyriproxyfen, an insect growth regulator (Royal Guard LLINs). The trial started in 2021 and will complete in 2023.

In a survey of close to 5,000 children aged 2–10 years from over 3,500 houses, we found that improved housing was strongly associated with a lower burden of malaria across a wide range of sites in Uganda. Overall, 15% of children living in improved houses tested positive for malaria, compared to 30% of those living in traditional houses. Housing modifications are being evaluated as an intervention to control malaria in Uganda and elsewhere, and should be considered as an important tool in our fight against malaria.

Saving children’s lives

Poorly children with severe anaemia aged five and under are 77% more likely to survive from malaria thanks to ongoing research and development across the Gambia, Malawi, Kenya and Uganda.

Young children hospitalised with severe anaemia not only have a high chance of dying while in the hospital, about one in six are at risk of dying within the first few months after they are discharged. Malaria is an important contributor.

Research with trials using Post Discharge Malaria Chemoprevention (PDMC) involving 3,600 children has seen the reduction in deaths by three-quarters. PDMC is now recommended by WHO to be provided to all children admitted with severe anaemia.

The team at LSTM led by Professor Feiko ter Kuile were involved in this study.

Research protects Mother and Baby from malaria during first trimester

Research coordinated by LSTM has helped the World Health Organization (WHO) improve its guidelines for treating malaria in pregnancy.

Malaria in pregnancy is a major threat to the mother and the developing fetus resulting in an estimated 10,000 deaths of the mother-to-be each year. The malaria parasite has found a clever way to stick to the placenta impairing the transfer of oxygen and nutrient to the growing fetus, which can cause the baby to be born too small, too early, or a pregnancy loss.

Prompt recognition and treatment with safe and effective drugs are therefore essential. However, it is often not known which drugs are safe to use in pregnancy, especially in the first three months (or first trimester), for fear of harming the fetus. This has resulted in many pregnant women with malaria in the first trimester being treated with old and ineffective drugs because insufficient safety data was available for newer, more effective antimalarials.

One such old drug is Quinine, which has to be taken three times per day for seven days and is associated with many side effects, such as ringing in the ears and dizziness. This can make it difficult for women to finish their treatment, which can have severe consequences for the pregnancy and the baby.

Researchers studied a group of newer medicines called ACTs (Artemisinin-based Combination Therapies) to see if they were safe to use during the first trimester of pregnancy. ACTs were already known to be safe in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters and much more effective than quinine.

They combined information on 35,000 pregnant women from multiple studies using data on treatment received in routine care. The outcomes of 750 women who had been treated with ACTs in the first trimester were compared to the outcomes of pregnancies treated with quinine in the first trimester. They found that women who were treated with an ACT were about 40% less likely to have a miscarriage or stillbirth or a baby born with congenital malformations than those treated with quinine.

The data was collected over 25 years as part of an excellent collaboration between researchers worldwide who shared their data, including those from Thailand and 11 sites in Africa. The results led the WHO to revise their malaria treatment guidelines which will benefit the over 120 million pregnancies occurring each year in malaria-endemic countries in Africa, south-east Asia and Latin America.

Podcast: Invest, innovate, implement for Zero Malaria: From lab to communities

In this episode, we celebrate World Malaria Day with our co-host and guests. This year's theme is Time to Deliver Zero Malaria, and it is focused on investing, innovating, and implementing tools that are available today and innovating for future tools.

WHO calls to action include prioritising funding for the most marginalised and hard to reach populations who are less able to access services and are the hardest hit when it comes to becoming ill from malaria.

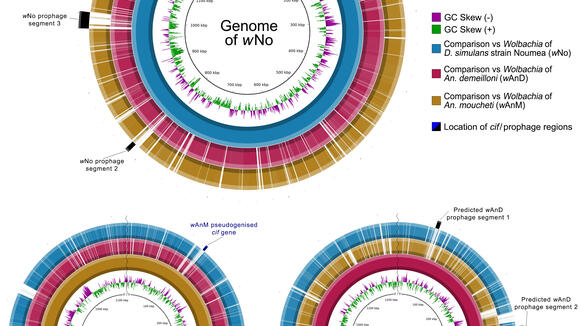

In discussion: LSTM's Dr Grant Hughes, Dr Tony Nolan from the Vector Biology department and co-hosted by Dr. Hellen Barsosio, who is in her final year of her PhD at LSTM Department of Clinical Science, where her PhD focuses on new drugs to prevent malaria in pregnancy.

The Malaria in Mothers and Babies (MiMBa) Pregnancy Exposure Registry

The Malaria in Mothers and Babies (MiMBa) Pregnancy Exposure Registry is a multi-country observational study with the aim to generate robust safety data on the use of the antimalarial Artemisinin-based Combination Therapies (ACTs) in all trimesters of pregnancy with a focus on the first trimester.

Data collection is ongoing in three sites in western Kenya (Homa Bay sub-county, Mfangano and Rusinga islands) and two sites in Burkina Faso (Nanoro and Soaw). These sites include 40 health facilities, and approximately 70,000 women of childbearing age are invited to participate in the study.

As of December 2022, more than 60,000 women (15-49 years) were enrolled in the study, and more than 12,000 pregnancies were detected in this cohort.

A robust data base has been set up so that safety information can be closely monitored, so that Mothers can receive appropriate health treatment. This helps to further reduce risks during her pregnancy.

World Malaria Day 2023 - LSTM Malaria in Pregnancy - the work of the team in LSTM Nigeria

Since 2020 LSTM has been working with the State Ministries of Health in Kaduna and Oyo and the State Primary Health Board in Kaduna (SPHCB) to improve maternal and child health by integrating quality HIV, TB, and malaria services in antenatal care (ANC) and postnatal care (PNC). The Global Fund programme with funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals aims to strengthen the provision of services for mothers and babies, and by that contributing to improving the health outcomes in the states of Kaduna and Oyo.

125 years of LSTM: Ronald Ross and the discovery of the transmission of malaria

On 20 August 1897 Ronald Ross made the historic link that female mosquitoes transmit malaria between humans. The discovery earned Ross the Nobel Prize for medicine.

Ross left the Indian Medical Service in 1899 to become the first senior lecturer, and subsequently Professor, at LSTM, the first institution devoted to tropical medicine anywhere in the world. His work at LSTM led to many distinguished honours and numerous expeditions to Africa, Asia and South America.

Ronald Ross set the foundation for scientists at LSTM and around the world to continue to make further discoveries and improved treatments for mosquito-borne diseases.