Ahmad Alcheikh. DTMH, September 2018

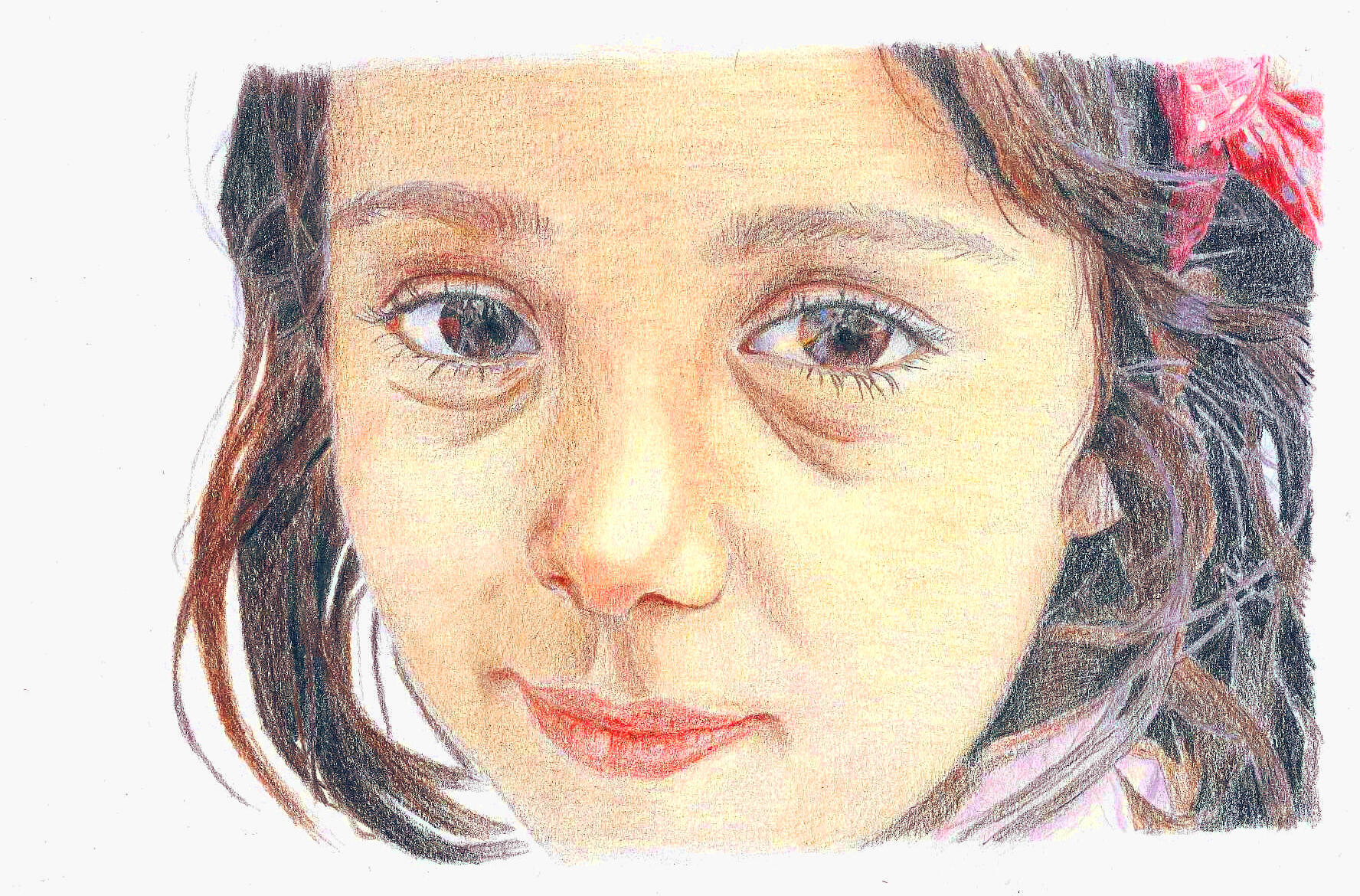

Recently we had lectures on refugee health and on torture survivors. It reminded me of a Syrian refugee camp in Turkey and a little girl (call her Zara).

Zara was about 5 years old.

In the time at camp she’d learnt another language playing with Kurdish refugee children. When we arrived with our kit she followed us with great interest. She was curious, and even wanted to help us with our work! There was a Kurdish man who could not communicate in any way with us. She interpreted his Kurdish to Arabic and we discovered what was bothering him. Despite being a refugee she was still smiling and laughing, and ran around playing with the other children. Somewhere inside a flame still lit her child-spirit.

How did Zara come to be hundreds of miles from home? It’s hard to imagine the sequence of events – the sound of bombs falling at night, the sight of rubble and broken homes, of separation from school friends or loved ones, of fear and hope, of the harsh side of humanity, and the kind. Up to 500,000 Syrians have died in this conflict and millions are internally or externally displaced.

Where does a little girl fit into this reality? Zara should be with her family at home. She should be attending school, learning maths and language, thinking up cheeky games, playing with the neighbours, having fun, and slowly forming her identity. She would be showing all the signs of a child who will excel. As it is, the odds are stacked so heavily against her. It was so sad to see such a bright child’s future being impeded in this way, and that she may never achieve her potential. You might say Zara’s world has failed her.

The World Health Organisation doesn’t define health as merely the absence of disease. The few camps I saw in Turkey were, medically, going okay. Diarrhoeal illnesses had subsided and the tents were arranged in some semblance of community. Yet, every adult there reported a deep, longing sort of sadness – and frustration. If we conducted a survey of blood pressures and organ function, we’d have a nice report. Somewhere, the human story is lost in numbers.

Our teachers tell us that the greatest determinants of health are not the provision of medical care, but the other things – social cohesion, poverty, politics, education, a safe environment, water and sanitation. No amount of medical provision could adequately restore a sense of normality, of dignity and psychological well-being to many of these families.

How can we quantify the effects of being dispossessed of home, friends, and community? Or of generations of children missing out on schooling? Or the pain of losing loved ones? How do we quantify the psychological damage that slowly builds, each time the sun sets on a tent so far from their actual home, wondering how it sets on the people they’ve left behind, and whether they’ve succumbed to the rubble they fled. How many generations will it take for things to ‘normalise’?

It’s easy to imagine refugees as extraordinarily resilient, patient, noble and virtuous people who always conquer their circumstances. But the reality is often less magical than that: they’re ordinary human beings, like the rest of us. When the news camera disappears, one is left with a tent, not a whole lot to do, but plenty of memories to mull on. Refugees share our strengths and our vulnerabilities. Why would they be any more patient or virtuous than we are? They complained of the frustrations of finding work; of the loss of dignity associated with being an involuntary guest; of tensions with the locals; of the contrast from leading normal lives to being dependant on others. We know how difficult loss of independence is, for example, in patients who have had a stroke. (To be clear, Turkey has the largest Syrian refugee population, over three million, counting only those who have registered: a remarkable feat of generosity).

It’s not always easy to understand a person who flees their home, or even the great yearning they must feel for it. Maybe it’s because the news stories seem so distant, so abstract. And it’s hard to feel 10 million displaced persons all at once. It’s easier to feel just one person, to meet them in real life, to laugh with them, to share a cup of tea on a straw mat, to look into their eyes and find that their life is just as meaningful as our own; that they too have hopes, aspirations, longing, frustrations, virtues, and weaknesses; and to feel their humanity in us and feel ours in them, and so feel their loss, and so desire to help them. Someone who has lost from their life someone they love very much might feel something of the sense of loss they must feel.

It’s great that there are places of refuge for war victims. But there is still plenty that can be done. You don’t need to be a nurse or doctor. Non-medical aid can save more lives than any health intervention. We might not fully feel the loss of a displaced person, but we can still make a difference. A good place to start is the United Nation’s agency responsible for assisting refugees (UNHCR). There’s always hope, and I think it’s a reflection of the human spirit in general that people can still laugh and have a good time, notwithstanding the above hardships.

While we were thus chatting over a hot tea, Zara and her friends ran around outside, playing and laughing, oblivious of the complexities of the world they’ve found themselves in. Hopefully she is still running, and for as long as possible.