Jagdeep Singh, DTMH 2016

Hi, I’m Jagdeep Singh. General Practitioner currently studying the Diploma in Tropical Medicine & Hygiene (DTM&H) course at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. My roots in this subject area stem from experiences in India, as a medical student, where I witnessed the reality of medical management coloured by extreme inequity in health and social care. These experiences were harrowing and resulted in my eagerness to learn more about health in resource-limited settings.

Born and raised in the Midlands, I completed my foundation training in Birmingham where I worked with a respiratory consultant specialising in TB and in public health with the Health Protection Agency. I went on to do my General Practice training in the neighbouring Black Country and after qualifying last year I worked in both areas which put me at the heart of two inner city communities with regular clinical contact with asylum seekers, migrants and settled minority groups.

This month you may have come across a briefing note from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees outlining the dire situation of refugees and migrants occupying a camp on the outskirts of Calais known as the Jungle and Dunkirk. This struck a chord with me after having worked as a volunteer with the Hummingbird Project in France. I found this experience to be very polarized, witnessing the poor conditions and seeing stark parallels with the slum settlements in India, it was hard to believe I was in the lap of Western Europe. Furthermore, an environmental health assessment carried out on the site in 2015, mirrored some of these sentiments.

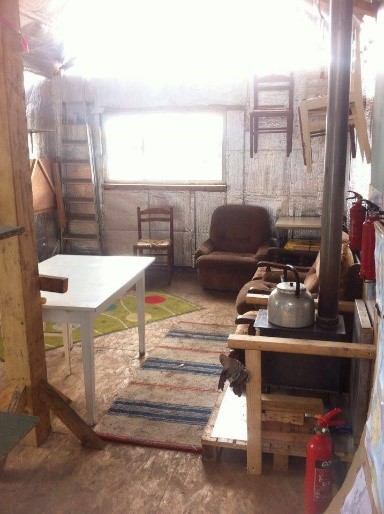

In France, I worked in a first aid clinic based in a semi-permanent shelter (Figure 1) treating minor injuries, managing conditions with a limited formulary, providing psychological support and triaging for other medical services. The patients I treated were Syrian, Afghani, Iraqi, Eritrean and Sudanese. No narrative that I heard suggested any of these people were economic migrants. Yep… just refugees here. In the wake of the tragic loss of Aylan Kurdi (the three year old Syrian boy whose body was found on the beach), the global community felt more could be done to protect children. Consequently at the clinic, the unaccompanied minor and adolescent pathway brought together vulnerable patients with volunteer legal experts and into the more sheltered areas of camp. This was the first step in supporting the legitimate claims to asylum through what is a complex web of bureaucracy.

The mental health of refugees was always a concern and the clinic was often used as a safe space. I recall one young Afghani male refugee who visited us, with his companion, one afternoon. They gave a graphic account of what they had left behind in Afghanistan, their horrific journey to the camp and how they had coped staying there.

I wrote the following words after this encounter:

This shelter cannot confine me.

My past does not define me.

A wound you cannot see was seared.

No longer oppressed by what I feared.

Nothing to lose.

Nothing to gain.

I smile and offer you a name.

A place, a story from where I came.

Do not cry or be ashamed.

Alive and not expecting world change.

Nothing to lose.

Nothing to gain.

I will not shout or scream in vain.

So I'm famished, its cold, there's squalor, there's rain.

I will still smile and offer you a name.

Seeing the indifference to the plight of the refugees was hard hitting and that day I ate some humble pie. Within the UK, I encounter those who feel our relief response needs to be more extensive whilst others feel we should be reaching out to our own populations needs first. However, they are not mutually exclusive for me. The Hummingbird doctors do this humanitarian work in their spare time, and I have been fortunate enough to be involved in some fantastic local community projects and know the challenge and dedication required serving our local populations as a GP. I believe these opportunities enrich our practice and give perspective, especially at a time when primary care services are being stretched and morale within the NHS is low.

The DTM&H course has been awash with meetings that have been inspiring, be it with students who have returned from remote and resource-poor settings or the lecturers who have an abundance of experience in the field. These encounters have also given me a better understanding of what I have seen. In a lecture series from Professor Joe Valadez, he highlighted the mandates of international organisations including the UN HCR and how they cooperate to respond to humanitarian needs. This gave me a more balanced opinion of the frustrations that volunteers can experience, desperately trying to mobilise resources in their area of need. Dr Tim O Dempsey led teaching on refugee health and managing victims of torture which reaffirmed how, as GPs, we need to be given more time with our patients, and to be sensitive to complex physical and psychological conditions. Recent talks from Dr Mary Lyons highlighted the importance of surveillance and primary care in a health care system. The challenges we face could not have been more explicit and thought-provoking.

The DTM&H course has allowed me to explore the areas of migrant health, public health and travel medicine which is relevant to my current practice in the UK. Once completed, I hope to volunteer in a community or primary care placement in a resource-poor setting.

To conclude, sharing the entirety of the Jungle experience is beyond the scope of a single blog post. I invited Dr C Bradshaw, a Clinical Fellow in A + E and a Hummingbird Doctor, to update on the current situation:

“In the last week there has been talk of prefecture-led evictions in the Calais camp, to include an area dominated by The Ashram Kitchen which serves over 1000 meals per day and contains two make-shift Mosques, a large area housing women and children, the vaccination centre and our Medical Clinic. This eviction will lead to mass ‘homelessness’ of around 3000 already vulnerable and cold individuals. The decision has been made by local Government to partially evacuate the southern portion of the camp. The aim is to manoeuvre 1,500 camp residents into the prefabricated containers (although residents are reluctant due to reported fingerprinting and registration.) The uncertainty of whether eviction will take place has caused a renewed swell of uncertainty within the camp. A legal case has now begun using the argument that eviction during the winter months is illegal in France. Our Hummingbird medical clinic will continue to open and remain in situ until further notice.”

In direct response to the above actions a new clinic has been constructed (Figure 2) which will be cooperatively used by the Hummingbird project and MSF. I leave you with a vlog from an MSF worker who went out to Calais earlier this year.