The LSTM story

Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine was founded in November 1898 - the first institution in the world dedicated to research and teaching in the field of tropical medicine.

Since then, we have been at the forefront of translational research and the training of leaders in global health.

Why was LSTM founded?

We were founded in response to a call from Joseph Chamberlain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies. Chamberlain called upon the General Medical Council and leading medical schools in the UK to engage in teaching and research into tropical diseases –including illnesses such as malaria and yellow fever. This was in response to the high mortality rate of colonial officers, white settlers and the city’s mercantile workforce which resulted in high costs to the Colonial Office and British government. Tropical diseases, such as malaria, came with substantial economic cost to the British Empire, and the government was keen to address the problem, though primarily interested in protecting colonisers and colonists.

Two schools were subsequently founded – one in Liverpool and the other, six months later, in London.

Why Liverpool?

Liverpool’s wealth and prominence was born out of its connections to the transatlantic slave economy. The city’s dominance of trade in Africa and the Americas during the 18th and 19th centuries saw the town transform from “a struggling port to become one of the richest and most prosperous trading centres in the world.” Once the East India Company lost its monopoly of trade between India (1813) and China (1833), Liverpool’s merchants quickly took up the opportunity to establish trade links with those regions. Trade with the colonies produced a wealthy, entrepreneurial class dominated by white European men and led to the city having strong connections to colonies in what was then defined as ‘tropical’ regions. Leading to Liverpool becoming the gateway to the British Empire.

The city’s shipping magnates recognised the threat posed by tropical diseases and many were receptive to the idea of a school to study them. There was a constant supply of cases of tropical diseases in the city's hospitals - in the year LSTM was founded Liverpool’s Medical Officer of Health reported 294 cases of malaria alone. LSTM was founded with a £350 contribution from Alfred Lewis Jones, alongside other wealthy merchants. While philanthropy was fashionable in Liverpool at the time, historical documents show that this initial donation was seen clearly by Lewis Jones as an investment and that he expected a financial return.

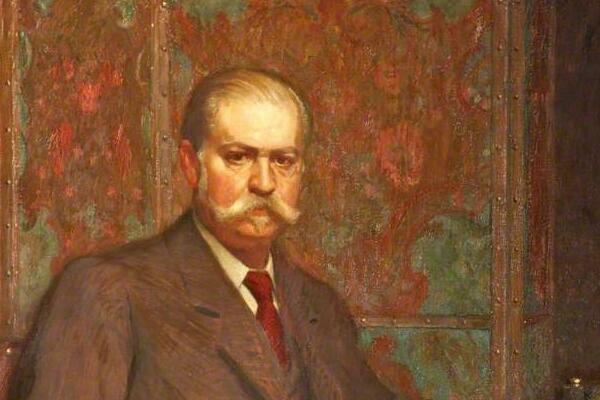

Who was Sir Alfred Lewis Jones?

Sir Alfred Lewis Jones was an influential shipping magnate who owned the Elder Dempster Shipping Line. He had made significant profits from various European countries’ colonial exploitations, mainly in Africa. The Congo Free State (now Democratic Republic of the Congo) was one such country, ruled and cruelly exploited at the time by the brutal King Leopold II of Belgium whose regime was responsible for the death of millions of Congolese people. Lewis Jones’ shipping company played a significant part in that exploitation, shipping goods such as rubber and ivory between Congo and Belgium, increasing his considerable wealth in the process.

In 1898 Lewis Jones offered a three-year contribution of £350 per year to the president of Liverpool's Royal Southern Hospital. The hospital, chosen due to its proximity to the docks trading with the colonies in the ‘tropics’ and the benefit it would bring to the shipping companies based there, accepted the offer, and planning began for what would become Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

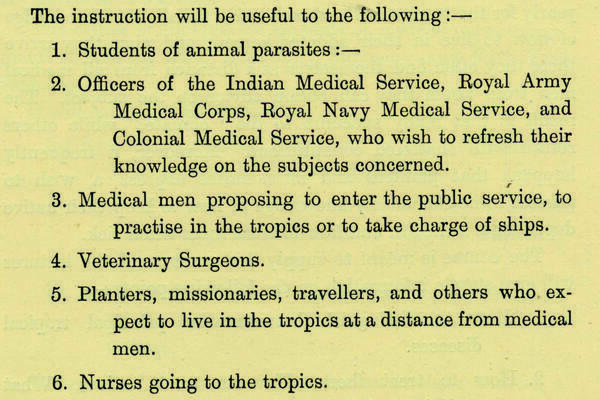

LSTM’s first prospectus

Published in 1899, made clear the school’s links with both local and international commerce and Britain’s colonies:

‘Owing to the short time period required for the passage between Liverpool and the tropical parts of Africa, to the interest taken by the great ship owners in the school, and to the large importation of cattle from America, a constant supply of examples of parasitic diseases of the higher animals can easily be obtained with a view to students being able at all times to examine the living organisms. The importance of this is very great… For the same reasons, communications with tropical colonies and scientific expeditions to Africa and elsewhere are easy to organise.’

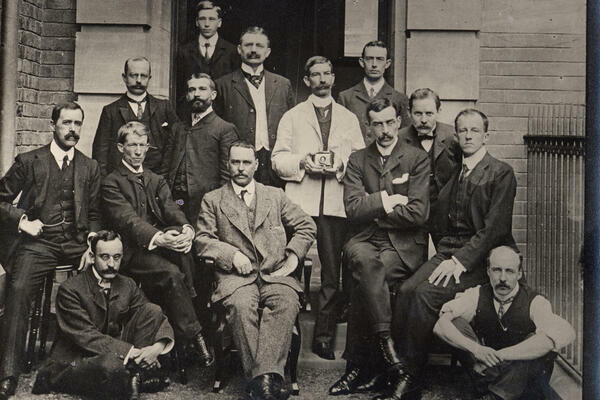

LSTM - the early years

LSTM received no central government funding, unlike the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, which opened shortly after. Instead, its founders raised the funds to set it up.

Rubert Boyce, Liverpool's city bacteriologist, was instrumental in shaping the new LSTM, becoming its inaugural director in 1898. He soon recruited the world-renowned Ronald Ross as LSTM's first lecturer in tropical medicine. Ross would later receive the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for discovering that malaria was transmitted by mosquitos – research that, like the founding of LSTM itself, was prompted by Britain’s desire to protect its colonists from disease. However, it also inspired a tradition in vector biology that is still strong today.

In its first decades, LSTM relied on the facilities of University College, now known as the University of Liverpool. This lasted until 1915 when its own purpose-built facility opened at Pembroke Place. However, World War I delayed full occupation until 1920 as the building was initially used as a military hospital.

Other notable staff at the time included Joseph Everett Dutton, who discovered one of the trypanosomes that causes sleeping sickness, Harold Wolferstan Thomas, who developed the first effective treatment for the disease, and his collaborator Anton Breinl, who later became ‘the father of Tropical Medicine’ in Australia. However, a colonial mindset was dominant at this time, and research has revealed that even luminaries such as Mary Kingsley – lauded as an ethnographer, writer, and explorer – were motivated by their support for the British Empire.

LSTM goes international

LSTM's first laboratory outside the UK was established in 1905 in Manaus, Brazil, replacing a succession of expensive research expeditions. Later, in 1921, Sir Alfred Lewis Jones' legacy funded the development (but not the running) of a research laboratory in Freetown, Sierra Leone, part of the British Empire at that time. Before its closure in 1941, the laboratory made some important discoveries, including demonstrating that a species of black fly was responsible for the transmission of filarial worms, which cause river blindness, in humans.

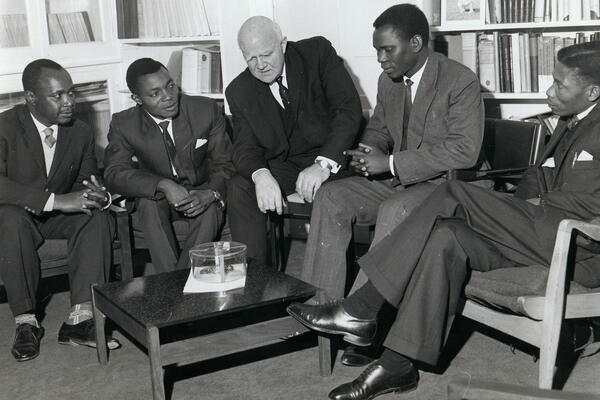

A change of focus

In 1946, the appointment of LSTM's longest serving dean, Brian Maegraith, marked a broadening of LSTM’s curriculum to take into account the needs of disease endemic countries. Maegraith famously declared, ‘Our impact on the tropics should be in the tropics!’ The school also forged links with research institutions across the globe, bringing research innovations to those most in need.

Maegraith was also pivotal in the creation of LSTM’s longest running research programme - the Far East Prisoners of War (FEPOW) project. This collaboration saw thousands of returning former prisoners of war treated for the physical and psychological illnesses from which they continued to suffer. It is a body of research which continues today.

Working in partnership

Our first female lecturer, Alwen Evans described herself and her colleagues as the specialists but LSTM’s partners across the world as the experts. That’s just one of the reasons why LSTM works closely with partners in-country and aims that all partnerships are equitable. Probably our most successful partnership is Malawi-Liverpool-Wellcome Trust (MLW) which aims to conduct high-quality research to improve health in Malawi and to train the country’s next generation of researchers. MLW recently turned 25.

Investment and expansion

Professor Janet Hemingway spearheaded a period of large investment and expansion when she became director of LSTM in 2001. This culminated in the school being awarded higher education institution status in 2013 and granted degree awarding powers in 2017.

Our current director, Professor David Lalloo, was appointed in 2019 and has overseen the school’s continued expansion and development. This period has included the COVID-19 pandemic when LSTM’s expertise came to the fore in the form of vaccine trials, treatments, diagnostics and fundraising for healthcare workers overseas.

In the Research Excellence Framework (REF 2021) LSTM was ranked second in the UK for the impact of our research and in 2022 we were designated as one of 21 world-leading specialist providers by the Office for Students. In 2023 we also received the UK’s highest national honour for higher education, the Queen’s Anniversary Prize, for our life saving Tsetse-control programme, Tiny targets.

Addressing our colonial past

Celebrating our 125-year anniversary from 2023 – 2024 provides us with a landmark opportunity to confront and research our institutional history and heritage, with digitalisation and decolonisation of our archive collections the first step in a long-term commitment.

Digitalisation and decolonisation of the collections will democratise access to information, decolonise colonial legacies, and empower us to talk about our history in an informed and evidence-led way. This forms one element of an overarching institutional History and Heritage Strategy which we will look to develop as a longer-term priority.

In the more immediate term, we will focus our efforts on a long-term colonial history research project led by experts (both academic and non-academic) who are affected by legacies of slavery and colonialism. Developing a rigorous public record of our history will create a vehicle for public engagement, widening participation and knowledge exchange. It will enable us to consider opportunities for meaningful restorative action, memorialisation, and decolonisation of the archives, education and research.

Since 2022 LSTM’s Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Manager, team, and Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) Staff Network have hosted a number of successful events to strengthen knowledge surrounding LSTM’s colonial history and archives. These events have been led by national and international experts and have provided rich learnings on how institutions with links to slavery and colonialism can tackle their history in a decolonial and anti-racist way, decolonising the archives and restorative action. The work supports LSTM’s strategic commitments to tackle racial inequity and become an anti-racist employer.

You can find links to these talks and panel events below:

- LSTM 2024 Black History Month Event – Decolonising and Liberating the archives: Race, Health and Tropical Medicine - YouTube

- Sandbach Tinne and Decolonisation of the Archives (talk by Malik Al Nasir)

- LSTM 2023 Black History Month Event – panel on ‘Understanding Colonial Legacies and Exploring Restorative Action’

- LSTM 2024 Anti-Racism Book Club Session 2 – King Leopold’s Ghost and LSTM’s relationship with the Congo (talk by Laurence Westgaph)

- Panel event on decolonising the archives centred on the film Free Renty – “Who owns the rights to the violence of the past? Is it the victim or the perpetrator? – Tamara Lanier”

Further Reading/Resources

Stephen Small. Reparations for Liverpool imperialism and West Africa. Writing on the Wall