Researchers from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) and Malawi have uncovered new evidence of zoonotic hybrid schistosome species infecting humans, raising concerns about schistosomiasis diagnosis and prevalence.

The study, published in the CDC’s Emerging Infectious Diseases, describes new cases of mixed intestinal and urogenital schistosomiasis in patients from Mangochi District, Malawi. Although the individuals tested positive for human urogenital schistosomiasis using standard urine diagnostic tests, their faecal samples also revealed many hybrid parasite eggs.

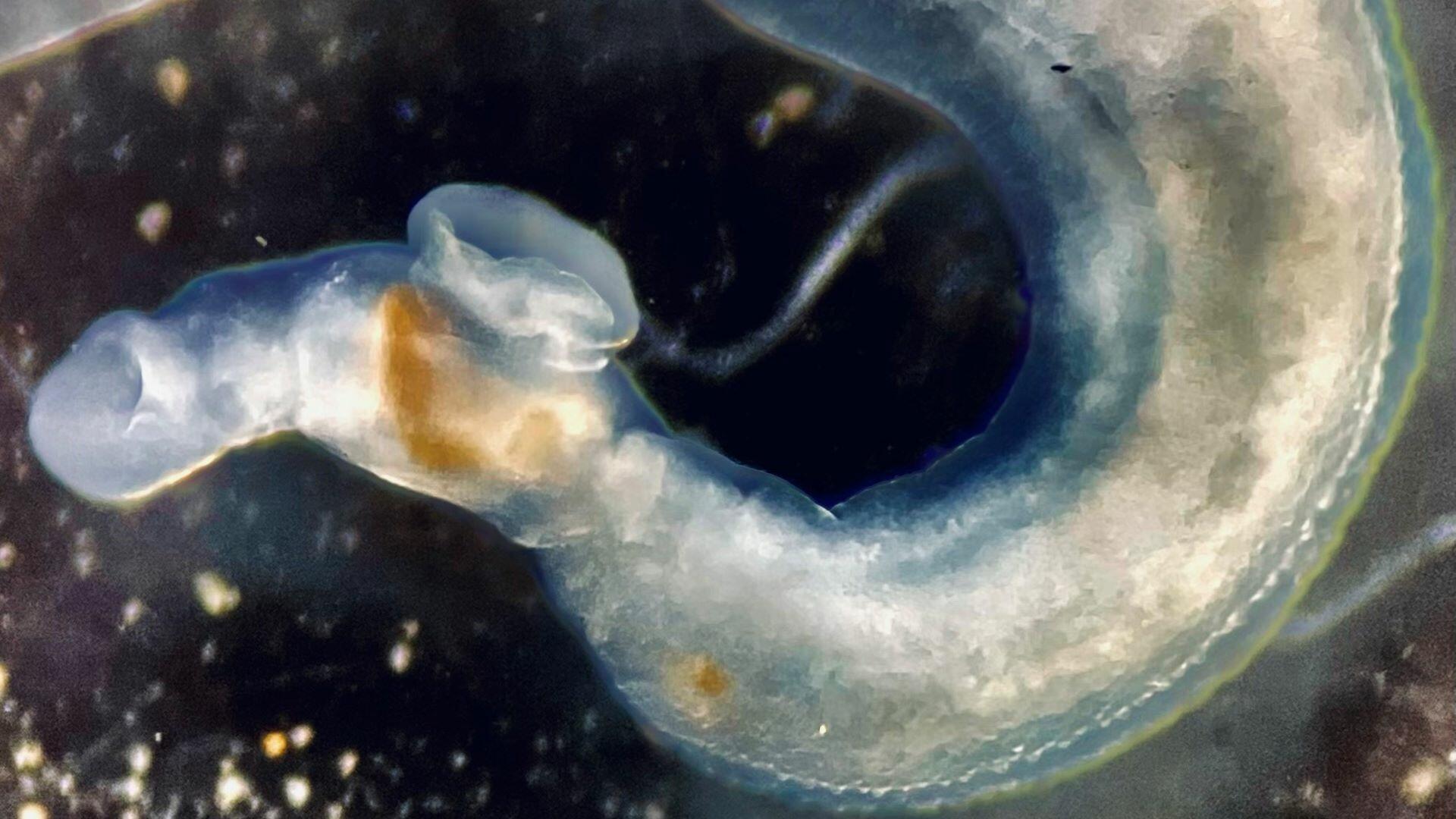

The eggs came from offspring of Schistosoma haematobium and S. mattheei, a livestock parasite, as well as evidence that S. mattheei had mixed with S. mansoni, the species normally associated with human intestinal infection.

These findings offer new insight into the growing complexity of schistosomiasis transmission where environmental changes and overlapping snail habitats have created conditions for cross-species hybridisation. They also call into question current diagnostics regimes advised by the World Health Organization (WHO) which rely on urine samples. The zoonotic hybrid species eggs were predominantly found in faecal samples, suggesting intestinal infections could be being missed.

Angus O’Ferrall, PHD candidate and lead author of the study, said: “WHO recommends using urine dipsticks to map intestinal disease, but the discovery of zoonotic and hybrid eggs in human intestinal tracts suggests that approach might be too narrow, and we may be missing hybrid intestinal infections.”

“Our findings point to the need for more comprehensive sampling strategies and expansion of testing recommendations in areas where humans and livestock share water.”

While hybridisation between schistosome species has been reported previously, this is the first evidence of S. haematobium group hybrids contributing to intestinal infection in humans.

The study calls for expanded surveillance in co-endemic areas, including routine examination of faecal samples alongside urine, and the deployment of molecular tools capable of identifying hybrid species. These steps are critical for ensuring accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Professor Russell Stothard, head of the HUGS Project (Hybridisation in UroGenital Schistosomiasis) at LSTM, added: “As we deepen our understanding of schistosome genomics, we must also adapt our field tools and public health strategies accordingly. Hybrid parasites are not just a scientific curiosity, they have real implications for control programmes, especially in settings with human-animal contact.”

The study’s authors stress the need for further research to determine the prevalence of zoonotic and hybrid schistosomes in Malawi and beyond, and to explore their impact on disease burden and control efforts.