It all started with a birthday party. Or rather, it all started with my daughter’s misfortune of having her birthdate bang-in the middle of the Easter break, causing difficulties for organising parties. Struggling for ideas, my co-parent and I opted for a Star-Wars themed kayak activity for children as a cool event. This is where the problems started.

Daughter (codename “R”) have never watched any Star-Wars, and was completely unfamiliar with the lore. How to explain lightsabres, imperial stormtroopers, or “the force” to a child in less than a month? Should we spend the entire Easter break watching the many films/TV/Cartoon options? (and if so, where to start? but that’s another topic).

Like a spaceship to the rescue, the Edinburgh Science Festival offered a children-oriented talk about “The Science of Star-Wars”, with the excellent Dr. Alex Baker from the University of Warwick. This gave ‘R’ some insights into the fiction, but also gave me an opportunity to reflect on how I can reach out to new frontiers and engage strange new publics on my topics of research and teaching.

Fast-forward a few weeks afterwards, and a message appeared on my LinkedIn page, looking for speakers in a ‘Science and Community’ stage for an upcoming Star-Trek convention. I am not (albeit my surname) a massive Star-Trek fan, but I have enjoyed the series as a teenager and recall their endless missions to save aliens and alien cultures from a series of diseases, disasters, or conflicts. Also, Star-Trek is famous for its ‘Prime Directive’, the guiding principle of non-intervention. Could I link these fictional situations to current debates in the humanitarian world about if, why, how, and how not, humanitarians can and should intervene on this planet? How similar are humanitarian core principles, like Neutrality and Impartiality, to Star-Trek Directives? And is this a case of life-imitating-art, or vice-versa?

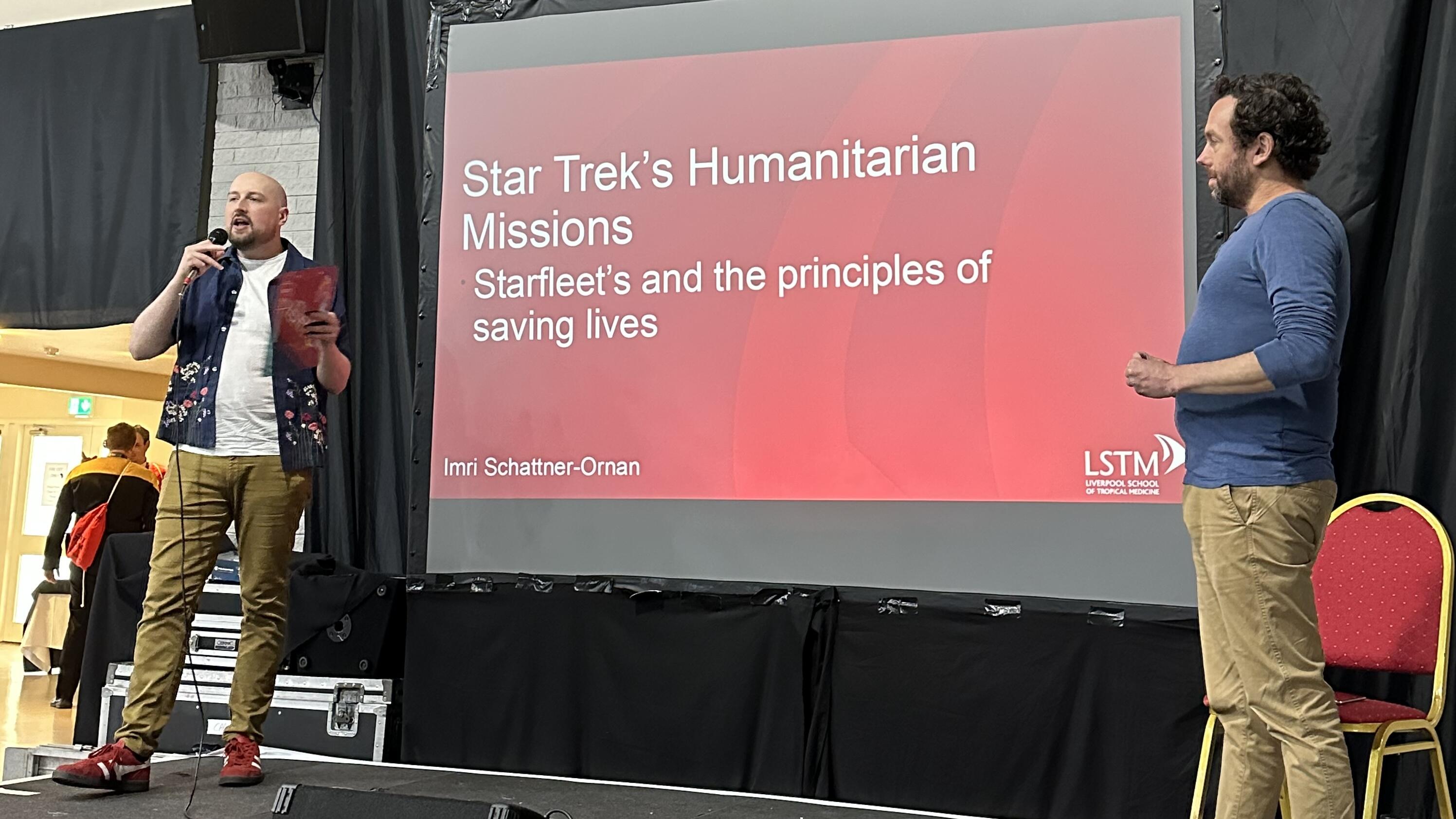

So, there I was, surrounded by dedicated fans in red/gold shirts of command staff (depending on the series), blue shirts of science officers, or dressed as one of many alien races of the Star-Trek universe, giving my talk and trying to draw parallels between humanitarians’ dilemmas, like the response to refugee camps in Eastern Zaire in 1994, and ethical questions faced by Captains Picard or Kirk on distant planets. It was an amazingly engaging experience, seeing the enthusiasm of the fans and their interest in how science-fiction can help us reflect about our planet and how our attitudes to things, like international interventions, have changed since the mid-1960s.

Humanitarianism is very much about problems in our planet. These problems are, almost entirely, the result of human activities, human conflicts, and political or economic decisions. So far, we have not been able to mess other planets up, though I can’t wait for that to happen. So, what can a Star Trek convention teach us about humanitarian topics, and is the word even correct for a universe full of aliens?

As an educator, it was a good lesson on how to make my topic, and what I care about, interesting and relevant to other people through what they care about. I don’t fully share their enthusiasm about Star Trek (though I felt humbled by their engagement), but if I can still find ways to share my interests and passion by understanding theirs better, we’ll all benefit. In a world that often feels like an echo-chamber, where different views are sometimes difficult to grasp and opposing views are sometimes frightening, there is something encouraging in seeing how mutual interests collide and how worlds come together.

As a humanitarian, the convention was a great opportunity to explore how popular culture impacts our life choices. I’ve met people who, because of their deep affection to Star Trek, choose careers in Science and Technology, and had conversations with people who were inspired by characters like Dr. Scully (from the X-files) to pursue interests in medicine and biology. What are the role-models that inspire humanitarians? And, if there are, what are the ethical issues they raise? In a context that popular western media often portrays in its centre White American/Europeans as the protagonists, how does that sits with the fact that most front-line humanitarians are from African, Asian, Middle Eastern or Latin countries, mostly working in their own countries and communities?

Bringing these ideas together, I feel there is a lesson there for me, as someone engaged in education, but also for my field. Humanitarians are suspicious of “heroism”, as it is often associated with “White Saviourism” complex, and ignorance about the causes of many of the world’s current illness (often related to colonialism, imperialism, capitalism and climate change). At the same time, we need role-models, real or imaginary, to engage us and others with humanitarian action.

Can we “borrow” models from Science-Fiction, Fantasy or other “unworldly” imaginations? If Dr. Scully can inspire someone to become a scientist, Indiana Jones to become an archaeologist, why not use Captain Picard or Princess Laia as an inspiration for humanitarianism? These characters are not without their faults, but we need them, or others, to inspire the next generation of humanitarians, and to help them aspire beyond the current challenges and frustration of the field.

There are few powers in the world that equal the power of fantasy. Like all powers, it invokes responsibility, and the risk of corruption. But if we can provide humanitarian fantasies, maybe we could also create humanitarian realities.