The climate crisis is fuelling increasingly extreme and catastrophic weather events.

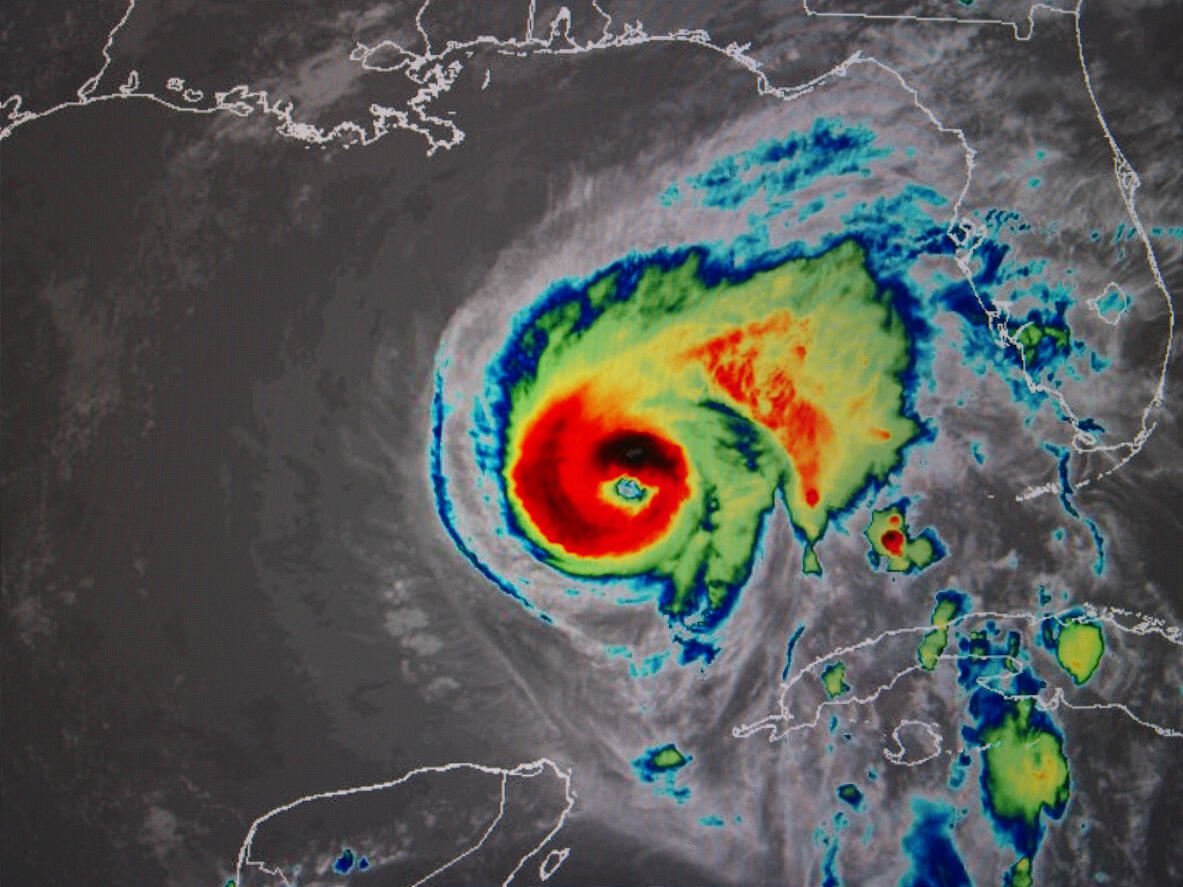

Just two weeks ago, the Caribbean was rocked by Hurricane Melissa, one of the strongest on record, while flooding, drought and intense heat are causing devastation across the world.

Research led by Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and The George Institute for Global Health India is focused on how these extreme weather events are affecting some of the world’s poorest and most marginalised urban communities. Through the lens of 10 communities in India, Kenya and Sierra Leone, the team are giving voice to the experiences of people directly affected, and supporting the resilience and responsiveness of health service delivery during these periods of shock.

Urban SHADE, led jointly by Professor Rachel Tolhurst from LSTM and Dr Surekha Garimella from The George Institute, India, also involves researchers from SDI-Kenya and three partners in Sierra Leone: Sierra Leone Urban Research Centre, Centre of Dialogue on Human Settlement and Poverty Alleviation and The Institute of Gender and Children’s Health Research.

As world leaders meet in Brazil for COP30 to discuss some of the most pressing global climate challenges, Professor Tolhurst explains why listening to the experiences of people and services at the sharp end of the climate crisis is essential to saving lives and improving care.

“At a time when global commitment to tackling the climate emergency is apparently wavering it is critical that global leaders listen to the people currently worst affected by the negative impacts of climate change, who overwhelmingly live in low and middle-income countries. The poorest and most marginalised communities globally have contributed the least to global emissions but are suffering the most devastating consequences. They also often have the greatest resilience and capacities for adaptation if supported with the necessary resources. Locally-led adaptation is vital because solutions to the challenges posed by our changing climate need to be appropriate to and owned by people affected in specific contexts.

We know that the negative health impacts of climate change affect the most marginalised and poorest urban communities, particularly the billion people living in informal settlements.

These communities often lack access to health services and are particularly vulnerable to poor health and wellbeing, particularly because of environmental risks created by limited water and sanitation infrastructure and precarious livelihoods.

The poorest and most marginalised communities globally have contributed the least to global emissions but are suffering the most devastating consequences

So when extreme weather events hit, including landslides, flooding, heatwaves and drought, the consequences can be particularly severe.

We are now nearly two years into the Urban SHADE project, and we’ve been collecting data and testimonies from people living in four cities in India, Kenya and Sierra Leone. This has included detailed information from local communities, how they live and work, their experiences and exposure to extreme weather events, and the impact of flooding, heavy rainfall and heatwaves on infrastructure and people’s health.

We have heard how extreme weather events affect people’s health, especially for those working outdoors and people living with disabilities.

One participant from a focus group in Andhra Pradesh, India, said: "We get dehydrated, suffer from fevers, and burnt skin - we don’t have a choice other than we have to keep working as summer is our peak earning season."

We have seen and heard how extreme weather events often damage and destroy houses and public infrastructure, displacing people and increasing the risks from disease.

An interviewee from Sierra Leone said: “When we are faced with a heavy storm in this community, the winds tear off our roofs. I used to think strong winds were just part of the rainy season but now I know it's getting worse because of climate change and how exposed our homes are."

Urban SHADE is also focused on how extreme weather events affect people’s access to health services. We have heard how flooding, roadblocks and infrastructure damages often cut off health services for the communities we are working with. This is particularly apparent where terrain is difficult, for example in hilly and steep Himachal Pradesh (India), where sick people need to be carried to ambulances during heavy rainfall and roads are cut off.

A lack of primary healthcare facilities can restrict preventive healthcare – and in one of our communities, flooding directly damages the healthcare facility.

An interviewee from Matopeni, Kenya, said: "That Kongowea dispensary is located in a flood plain because when it floods, the medicines are even carried away by water.”

Extreme heat was too reported to damage supplies, such as drugs and vaccines.

These communities often lack access to health services and are particularly vulnerable to poor health and wellbeing, particularly because of environmental risks created by limited water and sanitation infrastructure and precarious livelihoods.

We have also spoken to health service officials about the constraints they face to meet the needs of their communities during extreme weather events, and also some of the innovative ways they are able to continue provision of care in difficult circumstances.

We will be taking our findings into discussions with health systems officials and communities in a collective and participatory manner, working with them to help design interventions appropriate to each site. These could include appropriate preparation and continuity of services, including back-up power, protection of medicines from flooding and establishment of medical camps or outreach during extreme weather events.

We will also look at delivery of early warning systems and other communications methods to inform people, as well as a system of identifying the most at-risk patients who require extra help during such events.

Over the next year we will develop and implement these interventions and evaluate how well they work, together with communities and people working within the health systems. We will communicate and share our findings with local communities, municipal and national health systems policy makers and globally to support policy and practices that centre marginalised urban communities in tackling the challenges posed by the climate crisis and to promote climate justice.”